Antibodies

Antibodies are proteins made by B cells (part of the body's immune system) with each B cell producing unique antibodies that recognize a specific epitope on the antigen. An antigen is any substance that provokes an immune response – something foreign or toxic to the body. An epitope is a distinct molecular surface of an antigen capable of being bound by an antibody; for proteins these are divided into two categories, conformational epitopes and linear or sequential epitopes, based on their interaction with the antigen. The normal function of an antibody is to bind foreign substances (antigens) and flag them for destruction. This ability of antibodies to recognize and bind an epitope on an antigen makes them an important tool in research and the clinical laboratory. In fact, more than 30 antibodies are currently used therapeutically.

Antibodies are proteins made by B cells (part of the body's immune system) with each B cell producing unique antibodies that recognize a specific epitope on the antigen. An antigen is any substance that provokes an immune response – something foreign or toxic to the body. An epitope is a distinct molecular surface of an antigen capable of being bound by an antibody; for proteins these are divided into two categories, conformational epitopes and linear or sequential epitopes, based on their interaction with the antigen. The normal function of an antibody is to bind foreign substances (antigens) and flag them for destruction. This ability of antibodies to recognize and bind an epitope on an antigen makes them an important tool in research and the clinical laboratory. In fact, more than 30 antibodies are currently used therapeutically.

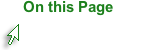

To generate an antibody the antigen (can be a whole protein or fragments of) are injected into an animal (often a mouse, rabbit, goat or donkey) several times over the course of several months. The key is the antigen must be different enough from the animal's own proteins to allow an immune response to be generated.

A polyclonal antibody actually refers to all the antibodies (IgG) that were in the serum of the host at the time the blood was collected. Since we have stimulated the immune system to produce antibodies, lots of B cells will be producing antibodies to many different epitopes on the antigen. Hence why it is called polyclonal.

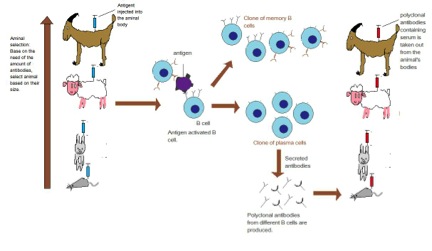

A monoclonal antibody is produced by one cell thus they all recognize the same epitope on the antigen. To produce a monoclonal antibody, tumor cells that can replicate endlessly are fused with B cells from an animal which has been stimulated with an antigen. The result of this cell fusion is a "hybridoma," which will continually produce antibodies.

Western Blotting

Western Blotting

The term "blotting" refers to the transfer of biological samples from a gel to a membrane and their subsequent detection on the surface of the membrane. Western blotting (also called immunoblotting because an antibody is used to specifically detect its antigen) is a routine technique for protein analysis. The specificity of the antibody-antigen interaction enables a target protein to be identified in the midst of a complex protein mixture in a semi-quantitative manner.

The term "blotting" refers to the transfer of biological samples from a gel to a membrane and their subsequent detection on the surface of the membrane. Western blotting (also called immunoblotting because an antibody is used to specifically detect its antigen) is a routine technique for protein analysis. The specificity of the antibody-antigen interaction enables a target protein to be identified in the midst of a complex protein mixture in a semi-quantitative manner.

The first step is to separate the macromolecules using gel electrophoresis (native or SDS-PAGE). After electrophoresis, the separated molecules are transferred to a membrane (usually nitrocellulose). As the membrane will bind any protein (including the antibody you will use to detect your protein of interest), after transferring the sample the membrane must be blocked with a common (cheap!) protein to prevent any nonspecific binding of antibodies to the membrane. Detailed procedures for detection of a protein on a Western blot vary widely. Most laboratories use a indirect detection method, in which a primary antibody is added first to bind to the antigen. This is followed by a labeled secondary antibody which recognizes the primary antibody. Labels include biotin, fluorescent probes, and enzyme conjugates that convert a substrate to a colored product thus staining the membrane.

ELISA (Enzyme Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay)

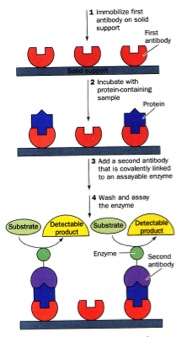

There are MANY forms of ELISAs! Most frequently used is the "sandwich" form in which an antibody is bound to a well in a microtiter dish. The sample is added, incubated, and then protein which were not captured by the antibody washed away. A labeled secondary antibody which recognizes a different part of the bound antigen can be used to quantify the amount of antigen in the sample.

There are MANY forms of ELISAs! Most frequently used is the "sandwich" form in which an antibody is bound to a well in a microtiter dish. The sample is added, incubated, and then protein which were not captured by the antibody washed away. A labeled secondary antibody which recognizes a different part of the bound antigen can be used to quantify the amount of antigen in the sample.